A collection of Japanese pickles. [Photographs: Miki Kawasaki]

It’s often said that a Japanese meal is built around three core foods: rice, soup, and pickles. Rice, plain and filling, is the main staple, so significant to the national cuisine that scarcely a meal goes by without it. Soup, miso-enhanced or otherwise, provides the comforts of umami—the appeal of a rich dashi broth is easy to understand. But pickles, in contrast, are a little less straightforward in their virtues. Tart, pungent, and often imbued with funky overtones, they are best enjoyed in small bites. In the context of the larger meal, they practically traverse the boundary between side dish and condiment.

Japanese pickles—known collectively as tsukemono—can easily go unnoticed as part of a washoku (traditional Japanese) meal. Yet they’ve rightfully earned their place as a cornerstone food because they serve an important purpose: Japanese food culture is heavily influenced by principles of balance handed down from kaiseki (the national haute cuisine). These principles suggest that a meal should contain a variety of colors, flavors, and cooking methods while taking into account sensory and aesthetic considerations. Tsukemono help create this harmony. They cleanse the palate and provide piquancy to counter the heaviness of umami-rich foods. Available in a number of bright hues, they also help fulfill the general rule that a meal should contain five colors: black, red, green, white, and yellow. And although they are altered by the processes of pickling, tsukemono are still considered to be raw. Think of them as salads with the added benefits of lactic-acid fermentation.

One further quality of tsukemono is that they are very much “transformed” foods, altered by the processes of pickling to the point where they barely resemble the fresh produce from which they are made. Many of the them are colorful and visually attractive, but hard to identify if you aren’t intimately familiar with Japanese cuisine. It’s entirely possible that you’ve had noodles topped with bright red beni shoga or curry rice with a side of chutney-like fukujinzuke and not quite known what those tangy bits and pieces were.

To guide you on your future travels through the world of traditional Japanese cuisine, we’ve pulled together some of the tsukemono you might encounter and the dishes they’re typically served with. While this list hardly represents the full range of pickles you can find in Japan—there are countless varieties and regional specialties—you’re likely to find these served with many of the the more well-known Japanese dishes, and even available for purchase in many Asian grocery stores.

Gari

Gari is probably the most widely known tsukemono because it is often served as a palate cleanser alongside sushi. The best gari is made with young ginger, which is naturally pink-hued around the edges—when brined, the slices take on that distinctive blushing color. Most commercial versions, however, use mature ginger, which is either left tan or dyed red with shiso leaf or artificial colorants.

How it’s made: Thinly sliced ginger is pickled in an amazuke marinade of sugar, salt, and rice vinegar for anywhere from a few hours to a couple weeks.

How it tastes: Clean and grassy, with sweet and peppery notes.

Serve it with: Sushi and sashimi or fried rice; the brine also makes a suitable dressing for salads and vegetables.

Takuan

Takuan is a crunchy daikon pickle named for the Zen monk credited with its invention. It’s distinguished by its bright yellow color, which can be achieved through the cultivation of bacillus subtilis bacteria during fermentation, heightened by the addition of persimmon peels, nasturtium flowers, or other coloring agents.

How it’s made: Daikon is sun-dried and salted before being placed in a container with nukadoko, a rice bran-based fermenting medium rich in bacillus subtilis. It’s then left to sit for anywhere from a few weeks to a few months.

How it tastes: Mildly tart and citrusy with a slight funk.

Serve it with: Plain rice, in bento boxes, and in maki rolls, either on its own or with fatty tuna. It’s also popular in Korea (where it’s known as danmuji), appearing inside kimbap rolls or with jjajangmyun (black bean noodles).

Umeboshi

Umeboshi are pickled plums known for their bracing saltiness and acidity—they’re so strong, they’ve been said to corrode aluminum lunch boxes. That intensity lends itself well to a number of handy uses. Samurai prized them as a means of combatting fatigue on the battlefield, likely because of the welcome jolt to the senses they provided. Even today, they’re recommended as a morning pick-me-up, defense against aging, cure for nausea, and remedy for hangovers.

How it’s made: Umeboshi making is associated with June, when both Asian plums and red shiso (which is used to color them) are ready to be harvested. They are potted with salt under a heavy weight during the summer rainy season (late June and July), exuding a briny liquid called umezu. Once the hot, dry days of August roll around, the umeboshi are allowed a few days to dry out in the sun. They are then repotted with a bit of the umezu and stored for a year or longer before eating.

How it tastes: Piercingly sour and salty, with a fleshy texture.

Serve it with: Onigiri (rice balls wrapped in nori); in bento boxes, an umeboshi placed in the center of a bed of plain rice is called a hinomaru, after the name for the Japanese flag; they can also be puréed into a paste, which makes a great maki roll filling with mountain yam and shiso leaf.

Beni Shoga

There’s a strong ethos throughout Japanese cooking of recycling ingredients and creating as little waste as possible. Beni shoga, bright red slivers of ginger, are one such example of ingredient reuse. They are made with umezu, the leftover brine from making umeboshi. Although some commercial varieties get their color from the added boost of artificial dyes, homemade beni shoga can turn a mesmerizing hue simply from the addition of the red shiso-tinted umezu.

How it’s made: Ginger is julienned and left to brine in umezu for anywhere from a few hours to a few days.

How it tastes: Zesty with a concentrated ginger flavor.

Serve it with: Tonkotsu ramen, okonomiyaki, yakisoba.

Shibazuke

A specialty of Kyoto, shibazuke is a mix of chopped cucumbers and eggplant that has been salted and brined with red shiso. It has a stunning purple-magenta hue that renders the vegetable pieces nearly unrecognizable from their original forms.

How it’s made: Historic recipes call for brining shibazuke for up to a year, but generally the pickles are made by letting them sit in salt until most of the liquid has leeched from the vegetable and the color has permeated throughout, which takes about a month.

How it tastes: Crunchy, crisp, and acidic, with a strong herbal note from shiso.

Serve it with: Plain rice, or with a few other tsukemono as a palate cleanser between bites.

Kyurizuke

Long, firm Japanese cucumbers, which have fewer and smaller seeds than their Western counterparts, are used to make many different types of tsukemono. These include cucumber pickles made with rice bran or miso, as well as asazuke, lightly seasoned quick pickles. One cucumber tsukemono you’re likely to find in Japanese grocery stores is aokyurizuke, which is marinated in soy sauce.

How it’s made: Japanese cucumbers are brined in a mix of soy sauce, salt, and sugar for one to two weeks until they have shrunk considerably and have a firm crunch.

How it tastes: Savory and salty, with a deep soy sauce flavor.

Serve it with: Donburi (rice bowls topped with meat), or in ochazuke (a dish made by pouring green tea over rice).

Fukujinzuke

Fukujinzuke literally translates to “lucky god pickles,” which is a reference to a Japanese myth about the seven gods of fortune. Some varieties accordingly contain seven different vegetables in homage. Although individual recipes vary, most contain lotus, daikon, eggplant, and cucumber. Some versions are tinted red with shiso.

How it’s made: The chopped vegetables are marinated in a mixture of soy sauce and sugar overnight or longer.

How it tastes: Sweet and chutney-like.

I am a huge fan of party snacks. When given the choice of a dessert table or an appetizer spread, I will always choose savory over sweet. Speaking of sweet… today I am so thrilled to be participating in a SURPRISE virtual baby shower for my beautiful friend Lauren of Keep it Sweet Desserts.

I am a huge fan of party snacks. When given the choice of a dessert table or an appetizer spread, I will always choose savory over sweet. Speaking of sweet… today I am so thrilled to be participating in a SURPRISE virtual baby shower for my beautiful friend Lauren of Keep it Sweet Desserts. Since I knew Lauren’s friends would be baking tons of fabulous desserts for our virtual baby shower, I decided to make a savory appetizer to balance out the sugar. Pickles in a Blanket are such a fun and EASY party appetizer that is perfect as we head into the holidays and the busy entertaining time of year.

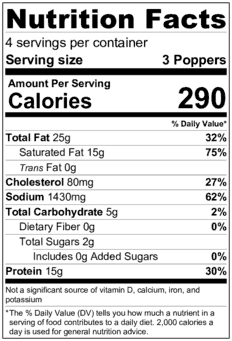

Since I knew Lauren’s friends would be baking tons of fabulous desserts for our virtual baby shower, I decided to make a savory appetizer to balance out the sugar. Pickles in a Blanket are such a fun and EASY party appetizer that is perfect as we head into the holidays and the busy entertaining time of year. Of course, pregnant women love pickles in all forms but who doesn’t? Salty, crunchy and low calorie, these bites are delicious with a cocktail but frankly they make a somewhat healthy, high protein, low carb and gluten free snack any day of the year. Win Win.

Of course, pregnant women love pickles in all forms but who doesn’t? Salty, crunchy and low calorie, these bites are delicious with a cocktail but frankly they make a somewhat healthy, high protein, low carb and gluten free snack any day of the year. Win Win.